Europol’s 2019 EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT), a product requested by the European Parliament and published today, provides a concise overview of the nature of the terrorist threat the EU faced in 2018.

Source: Daily Express. Holidays 2019: The FCO has mapped the most dangerous holiday destinations in Europe

New EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Report describes terrorist incidents and activities on European soil.

In 2018, terrorism continued to represent a major security threat in EU Member States. Horrific attacks killed thirteen people and injured many more. A stark increase in the number of arrests linked to right-wing extremism, although still relatively low, indicates that extremists of diverging orientation increasingly consider violence as a justified means of confrontation. Compared to 2017, the number of attacks and victims in the EU dropped significantly. However, the number of disrupted jihadist terrorist plots increased substantially. The level of threat from terrorism has therefore not diminished; if anything it has become more complex.

“Terrorists not only aim to kill but also to divide our societies and spread hatred. That feeling of insecurity that terrorists try to create must be of the greatest concern to us. Increasing polarisation and the rise of extremist views is a concern for EU Member States and Europol”, said Catherine De Bolle, Europol’s Executive Director. “I am confident that the efforts of law enforcement, security services, public authorities, private companies and civil society have substantially contributed to the decrease in terrorist violence in the EU. Terrorism affects real people and that is why we will never stop our efforts to fight terrorism and to prevent victims.”

In 2018, terrorism continued to represent a major security threat in EU Member States. Horrific attacks killed thirteen people and injured many more. A stark increase in the number of arrests linked to right-wing extremism, although still relatively low, indicates that extremists of diverging orientation increasingly consider violence as a justified means of confrontation. Compared to 2017, the number of attacks and victims in the EU dropped significantly. However, the number of disrupted jihadist terrorist plots increased substantially. The level of threat from terrorism has therefore not diminished; if anything it has become more complex.

“Terrorists not only aim to kill but also to divide our societies and spread hatred. That feeling of insecurity that terrorists try to create must be of the greatest concern to us. Increasing polarisation and the rise of extremist views is a concern for EU Member States and Europol”, said Catherine De Bolle, Europol’s Executive Director. “I am confident that the efforts of law enforcement, security services, public authorities, private companies and civil society have substantially contributed to the decrease in terrorist violence in the EU. Terrorism affects real people and that is why we will never stop our efforts to fight terrorism and to prevent victims.”

Dimitris Avramopoulos, EU Commissioner for Migration, Home Affairs and Citizenship, added: “While Member States together with Europol have become increasingly effective in preventing terrorist attacks on European soil over the past years, the terrorist threat is still there. Today’s report shows that the threat of violent extremism, from whichever ideology, is heterogeneous and nimble, and continues to thrive off the internet. More than ever, the EU needs to continue its counter-terrorist measures, information sharing and law enforcement cooperation both on the ground and online, with the crucial support of Europol.”

Julian King, EU Commissioner for the Security Union, concluded: “Europol’s report underlines that terrorism still poses a real and present danger to the EU. While our joint work to disrupt and prevent attacks seems to be having a positive effect, the enduring threat posed by Islamist groups like Da’esh, along with the rise of far right-wing extremist violence, clearly shows that there is still much to be done – notably in tackling the scourge of terrorist content online.”

Julian King, EU Commissioner for the Security Union, concluded: “Europol’s report underlines that terrorism still poses a real and present danger to the EU. While our joint work to disrupt and prevent attacks seems to be having a positive effect, the enduring threat posed by Islamist groups like Da’esh, along with the rise of far right-wing extremist violence, clearly shows that there is still much to be done – notably in tackling the scourge of terrorist content online.”

MAIN TRENDS

>Thirteen people lost their lives as a result of terrorist attacks in the EU in 2018. All the attacks were jihadist in nature and committed by individuals acting alone, targeting civilians and symbols of authority. Often, the motivation of the perpetrator and the links to other radicalised individuals or terrorist groups remained unclear. Mental health issues contributed to the complexity of the phenomenon. Completed jihadist attacks were carried out using firearms and unsophisticated, readily available weapons (e.g. knives).

>In addition to the completed attacks, EU Member States reported 16 foiled jihadist terrorist plots, illustrating the effectiveness of counter-terrorism efforts. The significant number of thwarted attacks and the so-called Islamic State’s continued intent to perpetrate attacks outside conflict zones indicate that the threat level across the EU remains high.

>Three disrupted terrorist plots in the EU in 2018 included the attempted production and use of explosives and chemical or biological materials. There was also an increase in the use of pyrotechnic mixtures to produce explosive devices in jihadist plots. A general increase of CBRN terrorist propaganda, tutorials and threats was observed and the barrier for gaining knowledge on the use of CBRN weapons has decreased. Closed forums proposed possible modi operandi, shared instructions to produce and disperse various agents and identify high-profile targets.

>In total, EU Member States reported 129 foiled, failed and completed terrorist attacks in 2018. The total number of attacks decreased after a sharp spike in 2017 (205), primarily because of the decrease in the reported ethno-nationalist and separatist-related incidents. Still, ethno-nationalist and separatist terrorist attacks continue to greatly outnumber other types of terrorist attacks (83 out of 129).

>In total 1056 individuals were arrested in the EU in 2018 on suspicion of terrorism-related offences (2017: 1219). One fifth of them were women. The number of arrests linked to right-wing terrorism remained relatively low (44 in 2018) and was limited to a small number of countries but increased for the third time in a row, effectively doubling for the second year in a row (2016: 12, 2017: 20). Right-wing extremists prey on fears of perceived attempts to Islamicise society and loss of national identity. The violent right-wing extremist scene is very heterogeneous across EU Member States.

>The number of European foreign terrorist fighters travelling, or attempting to travel to conflict zones was very low in 2018. The focus of jihadist networks has shifted towards carrying out activities inside the EU. The number of individuals returning to the EU also remained very low. Hundreds of European citizens – including women and minors, mainly of very young age- remain in detention in the Iraqi and Syrian conflict zone. All men and some women are believed to have received weapons training, with men also acquiring combat experience. While minors are essentially victims, there are concerns among EU Member States that they may have been exposed to indoctrination and training in former IS territories and may pose a potential future threat.

There is continued concern that individuals with a criminal background, including those currently imprisoned, are vulnerable to indoctrination and might engage in terrorist activities.

>Despite the shrinking of its physical footprint, IS succeeded in maintaining an online presence largely thanks to unofficial supporter networks and pro-IS media outlets. Pro-IS and pro-al-Qaeda channels promoted the use of alternative platforms and open source technologies. While IS online propaganda remained technologically advanced, and hackers appeared to be knowledgeable in encrypted communication tools, the groups’ cyber-attack capabilities and techniques were rudimentary. In addition, no other terrorist group with a demonstrated capacity to carry out effective cyber-attacks emerged in 2018.

>EU Member States assess that the diminishing territorial control of IS is likely to be replaced by increased al-Qaeda efforts to reclaim power and influence in some areas. Al-Qaeda affiliates exploited political grievances on the local and international level, including in messages directed at European audiences.

The report also provides an overview of the terrorist situation outside the EU, including in conflict zones like Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria but also the Americas, Australia, Russia and Central Asia, West Africa, South Asia etc.

>Thirteen people lost their lives as a result of terrorist attacks in the EU in 2018. All the attacks were jihadist in nature and committed by individuals acting alone, targeting civilians and symbols of authority. Often, the motivation of the perpetrator and the links to other radicalised individuals or terrorist groups remained unclear. Mental health issues contributed to the complexity of the phenomenon. Completed jihadist attacks were carried out using firearms and unsophisticated, readily available weapons (e.g. knives).

>In addition to the completed attacks, EU Member States reported 16 foiled jihadist terrorist plots, illustrating the effectiveness of counter-terrorism efforts. The significant number of thwarted attacks and the so-called Islamic State’s continued intent to perpetrate attacks outside conflict zones indicate that the threat level across the EU remains high.

>Three disrupted terrorist plots in the EU in 2018 included the attempted production and use of explosives and chemical or biological materials. There was also an increase in the use of pyrotechnic mixtures to produce explosive devices in jihadist plots. A general increase of CBRN terrorist propaganda, tutorials and threats was observed and the barrier for gaining knowledge on the use of CBRN weapons has decreased. Closed forums proposed possible modi operandi, shared instructions to produce and disperse various agents and identify high-profile targets.

>In total, EU Member States reported 129 foiled, failed and completed terrorist attacks in 2018. The total number of attacks decreased after a sharp spike in 2017 (205), primarily because of the decrease in the reported ethno-nationalist and separatist-related incidents. Still, ethno-nationalist and separatist terrorist attacks continue to greatly outnumber other types of terrorist attacks (83 out of 129).

>In total 1056 individuals were arrested in the EU in 2018 on suspicion of terrorism-related offences (2017: 1219). One fifth of them were women. The number of arrests linked to right-wing terrorism remained relatively low (44 in 2018) and was limited to a small number of countries but increased for the third time in a row, effectively doubling for the second year in a row (2016: 12, 2017: 20). Right-wing extremists prey on fears of perceived attempts to Islamicise society and loss of national identity. The violent right-wing extremist scene is very heterogeneous across EU Member States.

>The number of European foreign terrorist fighters travelling, or attempting to travel to conflict zones was very low in 2018. The focus of jihadist networks has shifted towards carrying out activities inside the EU. The number of individuals returning to the EU also remained very low. Hundreds of European citizens – including women and minors, mainly of very young age- remain in detention in the Iraqi and Syrian conflict zone. All men and some women are believed to have received weapons training, with men also acquiring combat experience. While minors are essentially victims, there are concerns among EU Member States that they may have been exposed to indoctrination and training in former IS territories and may pose a potential future threat.

There is continued concern that individuals with a criminal background, including those currently imprisoned, are vulnerable to indoctrination and might engage in terrorist activities.

>Despite the shrinking of its physical footprint, IS succeeded in maintaining an online presence largely thanks to unofficial supporter networks and pro-IS media outlets. Pro-IS and pro-al-Qaeda channels promoted the use of alternative platforms and open source technologies. While IS online propaganda remained technologically advanced, and hackers appeared to be knowledgeable in encrypted communication tools, the groups’ cyber-attack capabilities and techniques were rudimentary. In addition, no other terrorist group with a demonstrated capacity to carry out effective cyber-attacks emerged in 2018.

>EU Member States assess that the diminishing territorial control of IS is likely to be replaced by increased al-Qaeda efforts to reclaim power and influence in some areas. Al-Qaeda affiliates exploited political grievances on the local and international level, including in messages directed at European audiences.

The report also provides an overview of the terrorist situation outside the EU, including in conflict zones like Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria but also the Americas, Australia, Russia and Central Asia, West Africa, South Asia etc.

More details and context can be found in the Europol’s 2019 EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT).

Tags :

al-Qaeda

Europol’s 2019 EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT)

jihadist terrorist plots

security threat in EU Member States

Summer 2019: most dangerous holiday destinations in Europe

Posted by Christopher Oscar de Andrés, on Friday, June 28th 2019 at 10:55

|

Comments (0)

Los 10 países del Este que han transitado por el proceso de la adhesión que estudiamos en este breve análisis –Chipre y Malta se les considera, efectivamente, un caso aparte– suman 1.078.000 Km2 y 105 millones de habitantes: se trata de cifras nada desdeñables. La nueva Europa cuenta actualmente con una población de 501.100.000 (1). No obstante, el PIB de los países del Este integrados –han dejado de ser candidatos– solo representa un 5% del PIB de la UE: el PIB per cápita del conjunto de los PECO representa, equiparando la capacidad adquisitiva de las monedas, un 39% de la media comunitaria. Como nos indica Benjamín Bastida (2) en su oportuno estudio, el retraso económico del Este equivale a una generación y la heterogeneidad extrema de esta nueva UE-27, debe afrontar de forma más ágil y en medio de una crisis financiera, que se extiende ya durante cinco años consecutivos, para subsanar la convergencia real como uno de los puntos de apoyo de la construcción paneuropea.

logotipo Croatian National Tourism Board

Frecuentemente se identifica la ampliación al Este como una cuestión política de gran valor simbólico y bajo interés económico. Cierto es que los ‘beneficios estáticos’ –supresión de distorsiones arancelarias, la posibilidad de explotación de economías de escala y, consecuentemente, optimización de la asignación de recursos…– son especialmente relevantes para los países PECO. No obstante, aún no se ha explotado todo el potencial de los beneficios/ventajas dinámic@s de la integración, que supone ese aprovechamiento del novísimo marco de referencia ligado, entre otros factores, a la reacción positiva de los agentes sociales que nos propone B. Bastida. A partir de la firma del Tratado de Niza (3), surgirán de forma efectiva unas nuevas normas del juego y oportunidades para la iniciativa proactiva y el federalismo creativo y constructivo.

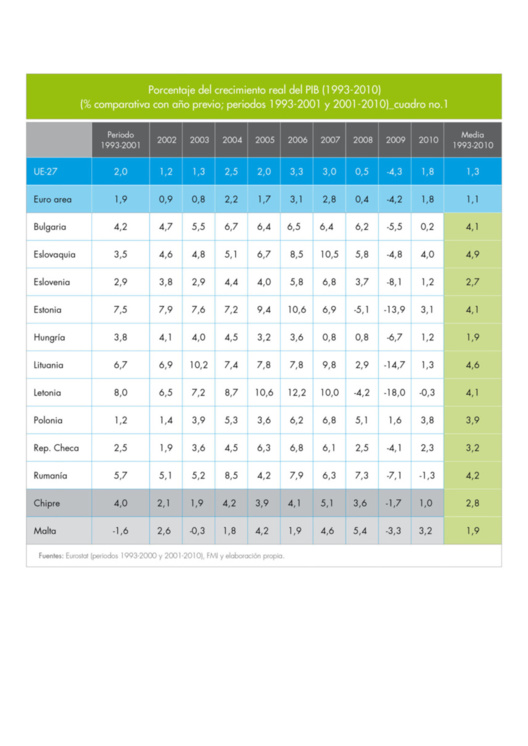

cuadro no.1

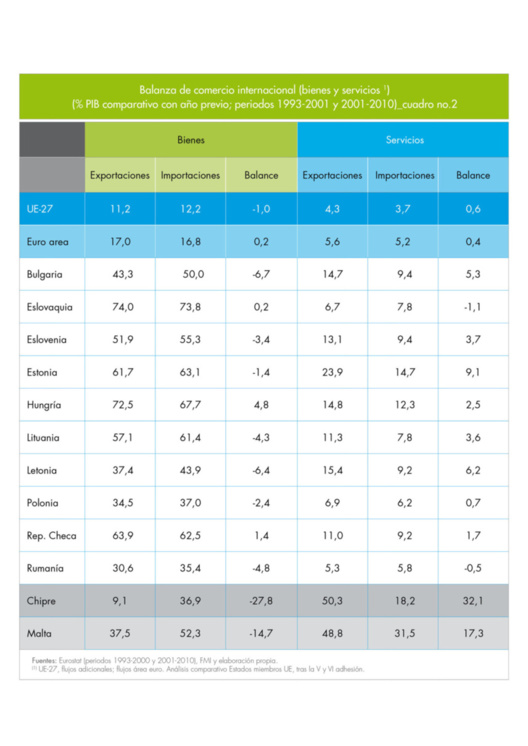

Admitamos que en términos de comercio exterior la integración ha progresado con extraordinaria agilidad, así como de forma asimétrica: incluye la vinculación creciente de las monedas nacionales al euro, el acercamiento institucional y legal al acervo comunitario y el desarrollo de los flujos comerciales, financieros, productivos o migratorios. Hasta el año 2010 el valor en euros de las exportaciones y los flujos de Inversión Externa Directa (IED) de la UE a los países del Este integrados se ha multiplicado por 5,6% –cuadro no.2– y el de las importaciones por 5,2%. Como resultado de este impulso, los 10 nuevos socios comunitarios se han convertido en el segundo socio comercial de la UE, a gran distancia aún de EEUU. Bulgaria; Eslovaquia; Estonia; Lituania; Letonia y Rumanía cuentan con un porcentaje de crecimiento de PIB hasta 2010 superior al 4% –cuadro no.1, véase especialmente balances de bienes y servicios– y los déficits del PIB de Polonia; Eslovenia; Hungría y R. Checa –oscilan entre 1,9% y 3,9%– se compensan de algún modo con los excedentes generados por su comercio exterior: para Hungría o Estonia sus transacciones comerciales externas con la UE representa más de un 70% del total de su comercio exterior. El stock de inversiones directas comunitarias en los países PECO sigue creciendo desde el 5% como punto de partida referencial, antes de su adhesión (año 2000). Las empresas y consumidores comunitarios también se han beneficiado de unas monedas infravaloradas que han permitido diversificar y abaratar los aprovisionamientos y de unos niveles de remuneración de la fuerza de trabajo sobre los tipos de cambio de mercado, que son los que determinan los costes, las cuentas de resultados de las empresas comunitarias y los precios de los artículos, alcanzando apenas una quinta parte de los costes laborales comunitarios –o un tercio de los españoles.

cuadro no.2

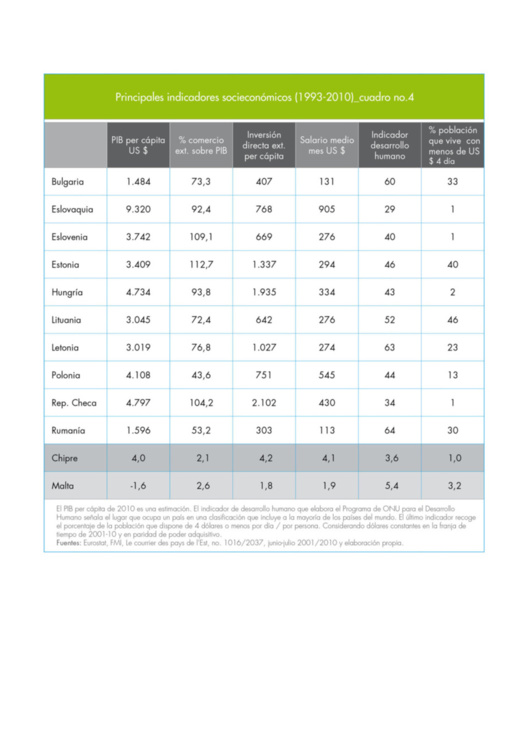

La integración económica, pese a los riesgos inmediatos ya surgidos (4), difícilmente podría haberse saldado con mayores beneficios para la UE-27, especialmente para algunos países miembros, como Alemania o Austria, territorios fronterizos con los nuevos socios. Desde la óptica de los países PECO, el saldo de la integración económica ya consolidada presenta perfiles más confusos: priman los resultados positivos en países como Eslovenia; Hungría; Polonia; o la República Checa. Mientras en otros casos puntuales –Bulgaria y Rumanía son los más evidentes– predominan las consecuencias negativas (5). La distribución de la renta e todos los países PECO muestra una clara tendencia al aumento de la desigualdad. En este sentido, muchos organismos internacionales –ej. Banco Mundial, FMI, UNICEF, etc.– muestran numerosos datos muy significativos que confirman que las condiciones de vida de una parte importante de la población de los países del Este se han degradado en los últimos años de manera evidente –véase cuadro no.4 (6). No obstante, ese deterioro de las condiciones de vida no ha impedido que las reformas sigan su curso vital. Con intensidad, nuevamente desigual, algunos países han aprovechado la mayor vinculación con las economías comunitarias para renovar y modernizar partes significativas de su aparato productivo; obtener financiación externa suplementaria; aumentar sus ventas al exterior; maximizar y diversificar la oferta de bienes de consumo en sus mercados nacionales y conseguir un crecimiento económico que ha beneficiado a una parte importante de su población activa. En otros países, en cambio, la integración ha agravado la destrucción de su tejido industrial y el empeoramiento de las condiciones de vida / trabajo de la mayoría, mientras que los progresos estabilizadores parecen demasiado precarios y la especialización productiva sigue siendo muy similar a la que predominaba en los sistemas tipo postsoviético. Nos parece vital evitar consolidar los ‘dos tipos de regiones subdesarrolladas’ que nos anticipan algunos analistas –ej. B. Bastida–, con la consiguiente integración final de los PECO en la buhardillas de la UE-27; apostando por la modernización industrial, en lugar de permitir que algunos países del Esta sufran el riesgo de fondo de atravesar por un proceso irreversible de desindustrialización.

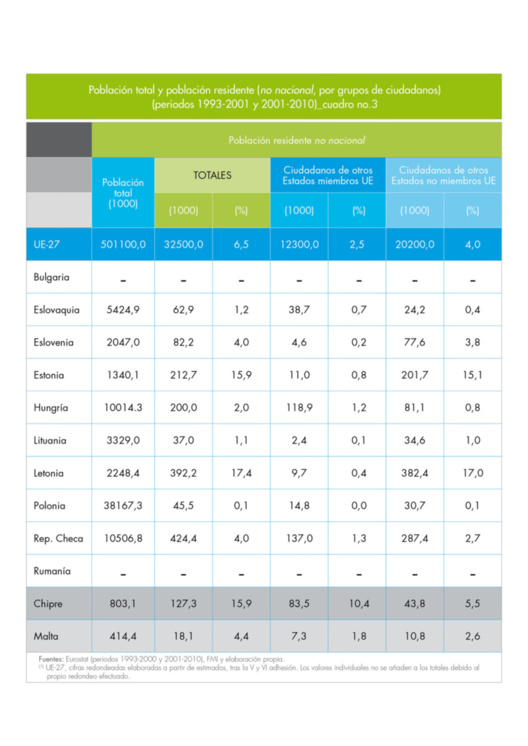

cuadro no.3

Hemos de destacar, como reflexión conclusiva, que el reto de la ampliación consiste en aprovechar los beneficios potenciales y convertir los riegos en oportunidades: la gestión eficaz de la crisis prolongada que nos continúa acechando; la eclosión de un nuevo orden europeo que lidere la geopolítica y el mercado global. Desde la propia Declaración Schuman –‘Europa no se hará de golpe ni será una construcción de conjunto’– resultaba evidente que el proyecto europeo requeriría de bastante tiempo y una buena dosis de ese término afín a la cultura anglosajona, ‘stamina’ –aguante / resistencia–, para consolidarse ya que, en último extremo, nos encontramos frente a un proceso continuado de adhesión de nuevos socios e implementación de nuevas entidades; una sedimentación que solo un tiempo prudente podría lograr. La frase tan común como falsamente atribuida a Monnet, ‘Si volviera a comenzar, lo haría por la cultura’, muestra el reflejo de la profundidad y, por tanto, cierta lentitud de los cambios requeridos para que la integración de la UE-27, en breve UE-28, cristalice. En consecuencia, los que abogamos por una Europa extrovertida y expandiendo sus fronteras hacia fuera, no lo hacemos desde una agenda intervencionista, como si pese a la crisis financiera tan acuciante y aparentemente contagiosa que se aferra a este presente corrosivo los europeos hubiéramos comenzado a desarrollar ansias de poder internacional. Más bien al contrario, lo hacemos desde el convencimiento, con más o menos espíritu europeísta, de que el tiempo ha dejado de jugar a favor de la Unión Europea, tanto política como históricamente: lo cual constata que el sentarse a esperar o aislarse del mundo no es una opción válida, si lo que quiere la UE-27 es fortalecer sus valores y su modelo, bien dentro del contexto geopolítico de los miembros de la UE ya consolidados, los nuevos socios, como los próximos socios que en un futuro se adhesionarán: ¡bienvenida Croacia!

cuadro no.4

Notas bibliográficas

(1) GASPARD, Michael (abril 2001): L’intégration des PECO. Scénario pour l’avenir, Le courrier des pays de L’Est, no. 1014, Bruselas.

(2) BASTIDA, Benjamín (2002): La Ampliación de la Unión Europea hacia los Países del Este, Revista electrónica Papeles del Este. No. 2, pp. 1-15 | http://www.ucm.es/BUCM/cee/papeles/02/07.pdf.

(3) Tratado de Niza: entró en vigor el 1 de febrero de 2003. | Véase CALDUCH CERVERA, Rafael (20-21.09.2001): ‘El Tratado de Niza no sólo ha regulado la futura composición de las diversas instituciones europeas de acuerdo con la ampliación a los doce futuros miembros, sino que también ha tenido que abordar el delicado problema de los procesos de decisión interinstitucional y la ampliación de los temas sometidos a la regla de la mayoría, todo ello en un marco general de riguroso respeto al entendimiento franco-alemán como fundamento político del proceso de integración’, p. 49. Véase también Tratado de Niza. Texto provisional aprobado por la Conferencia Intergubernamental sobre la reforma institucional- SN 533/00 ES, tabla temática no. 6.

(4) BASTIDA, Benjamín (2002 – apunte bibliográfico no. 19): estos son 1) Los déficits estructurales en la balanza que siguen constituyendo un riesgo para la estabilidad macroeconómica; 2) La insuficiencia presupuestaria de los gobiernos miembros para afrontar la ampliación; y 3) La cohesión insuficiente que ya ha doblado el gap entre países como Alemania y Rumanía.

(5) Véase LUEGO, F. y FLORES, G. (2001): Cambio estructural y transformación industrial en los países poscomunistas de Europa central y oriental. Revista electrónica ‘Papeles del Este. Transiciones poscomunistas’. No.1.

(6) Los costes sociales de la transformación sistémica pueden sintetizarse en un dato escalofriante: la población que vive por debajo del umbral de la pobreza (menos de 4 US$/diarios por persona) se ha multiplicado por 12, pasando de 14 a 168 millones. Los países pobres son actualmente mayoría entre aquellos que pertenecían al antiguo Bloque Soviético. Aunque con una distribución muy desigual: en la mayoría de los países de la antigua URSS superan el 50% de la población total; en Polonia / los Balcanes / los países Bálticos suponen entre un 13%-46%. Mientras que en el resto de la Europa Central apenas alcanza un 1%-2%. Véase cuadro no.4, Anexos.

(1) GASPARD, Michael (abril 2001): L’intégration des PECO. Scénario pour l’avenir, Le courrier des pays de L’Est, no. 1014, Bruselas.

(2) BASTIDA, Benjamín (2002): La Ampliación de la Unión Europea hacia los Países del Este, Revista electrónica Papeles del Este. No. 2, pp. 1-15 | http://www.ucm.es/BUCM/cee/papeles/02/07.pdf.

(3) Tratado de Niza: entró en vigor el 1 de febrero de 2003. | Véase CALDUCH CERVERA, Rafael (20-21.09.2001): ‘El Tratado de Niza no sólo ha regulado la futura composición de las diversas instituciones europeas de acuerdo con la ampliación a los doce futuros miembros, sino que también ha tenido que abordar el delicado problema de los procesos de decisión interinstitucional y la ampliación de los temas sometidos a la regla de la mayoría, todo ello en un marco general de riguroso respeto al entendimiento franco-alemán como fundamento político del proceso de integración’, p. 49. Véase también Tratado de Niza. Texto provisional aprobado por la Conferencia Intergubernamental sobre la reforma institucional- SN 533/00 ES, tabla temática no. 6.

(4) BASTIDA, Benjamín (2002 – apunte bibliográfico no. 19): estos son 1) Los déficits estructurales en la balanza que siguen constituyendo un riesgo para la estabilidad macroeconómica; 2) La insuficiencia presupuestaria de los gobiernos miembros para afrontar la ampliación; y 3) La cohesión insuficiente que ya ha doblado el gap entre países como Alemania y Rumanía.

(5) Véase LUEGO, F. y FLORES, G. (2001): Cambio estructural y transformación industrial en los países poscomunistas de Europa central y oriental. Revista electrónica ‘Papeles del Este. Transiciones poscomunistas’. No.1.

(6) Los costes sociales de la transformación sistémica pueden sintetizarse en un dato escalofriante: la población que vive por debajo del umbral de la pobreza (menos de 4 US$/diarios por persona) se ha multiplicado por 12, pasando de 14 a 168 millones. Los países pobres son actualmente mayoría entre aquellos que pertenecían al antiguo Bloque Soviético. Aunque con una distribución muy desigual: en la mayoría de los países de la antigua URSS superan el 50% de la población total; en Polonia / los Balcanes / los países Bálticos suponen entre un 13%-46%. Mientras que en el resto de la Europa Central apenas alcanza un 1%-2%. Véase cuadro no.4, Anexos.

Category

Recent posts

Archives

#Team Management #Gestión de Equipo International Business Development #Gestión de Equipo Comercial

5 MISSION AREAS IN HORIZON EUROPE

Acceso universal al tratamiento del sida

ACNUR

actor Pepe Sancho

ADHESIÓN DE CROACIA A LA UE

advertising / teleshopping spots

Africa

Alianza Atlántica

Alianza del Pacífico

Alibaba

Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.

AlipayApp

Amnistía Internacional

Ana Pastor

AnálisisyGestiónInteligenteDeDatos

Angela Merkel

Banco Central Europeo (BCE)

Banco Mundial

Barack Obama

batalla del sector del taxi y VTC

Benjamin Franklin

Bill Gates

binomio chavismo / antichavismo

Blockchain opportunities in international public health care sector

Blockchain technologies in health care

Blog Posts

Boris Johnson

Brexit

BUILDING THE CITIES OF THE FUTURE

China

Comisión Europea

Coronavirus

Covid-19

COVID-19

Cybercrime

David Cameron

Editorial Universitas SA

EU Convention of Human Rights

European Commission

FMI

Henrique Capriles

Human Rights

ICAA

International Business Development

Jack Ma

Jean-Claude Juncker

Mariano Rajoy

Obama

ONU

OSCE

The Council of Europe

Thomas Hammarberg

UNED

UNHCR

Unión Europea

Vladímir Putin